“We should show the world how beautiful nature is.”

SUMMARY

Climate anxiety is becoming an increasing threat to the mental well-being of youth around the world—negative thoughts and feelings which, if left unchecked, could lead to individual health problems and a generational struggle to find solutions to climate change. In a 2021 survey of 10,000 young people aged 16 to 25 in ten countries, 50% said they felt sad, anxious, angry, powerless, helpless, and guilty, and 45% said their feelings about climate change negatively affected their daily life and functioning. (Marks, 2021)

Thus, supporting young people in managing their stress and engaging them in positive ways on climate issues becomes a social and moral imperative. L’Université dans la Nature (UdN) has formed a nature-based solution to this global issue with the creation of their youth education program, The Forest and I. The objective of the program is to leave students feeling empowered, positive, and connected through a guided forest experience.

This program, fully supported by the l’Oeuvre National de Secours Grande-Duchesse Charlotte, was first presented to two classes in Spring 2022, after which it was adapted and presented to thirteen more classes during the Fall 2022 and Spring 2023 semesters. Testimonials and feedback reveal an experience that met the program’s initial objectives—participants learned more about the natural world, communicated feelings of connectedness with it, and reported a greater sense of relaxation and tranquility. The following report details the program’s development, goals, outcomes, and future adaptations.

INTRODUCTION

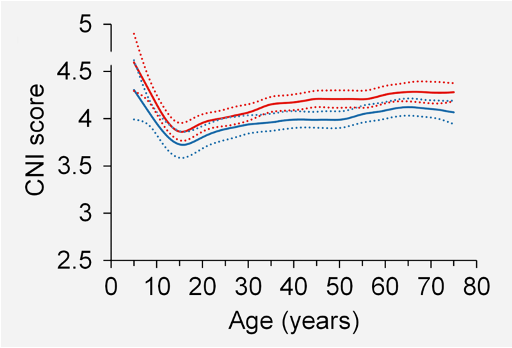

Child development experts have studied the close connection with nature that exists during youth. It is a relationship that we tend to lose as we grow into our teenage years and beyond. In fact, research shows that, on average, the disconnection from nature is greatest during teenage years— greater than at any other age during our lives.

Figure 1. Predicted Connection to Nature Index (CNI) scores for ages 5-75 from generalized additive models (GAMs) for females (red) and males (blue) with 95% confidence intervals (dotted lines). CNI scores ranged from 1 to 5. (Hughes J., Rogerson M., Barton J., & Bragg, R., 2019)

UdN research with students bears this out—in one survey, not a single student reported occasionally visiting a forest. Why does the connection fade during the teen years and, most importantly, can it be rekindled? The results of the Forest and I program reveal that the answer is yes.

Many participants of the program said they greatly enjoyed their time in the forest, and would recommend it to their peers. Some reported valuing nature more than they did previously, and many reported feeling better at the end of the activity than they did at the beginning. The wish to spend more time in nature, and learn more about it, was also expressed. This feedback is a strong indicator of the successful achievement of the program’s key objectives—boosting the connection with nature, reducing climate anxiety, and instilling feelings of empowerment.

PROGRAM PHILOSOPHY

The program was developed as an extension of the UdN mission to re-connect humans with nature. Specifically, the UdN endeavor to take clear scientific evidence on the positive impacts of nature and put it into practice within educational settings was realized through the development and delivery of The Forest and I. In particular, the program supports the organization’s value pillars of education and reconnection.

PROGRAM APPROACH

The initial goal was to deliver a program lasting four hours which would leave youth participants with a clear understanding of the benefits nature has on our health. After consulting with teachers on program design, it became quickly apparent that students’ disconnection from nature, though expected, was far greater than initially assumed. A combined theoretical and experiential approach which guided students to explore their attitudes about the natural world, as well as their personal relationship with it, was deemed necessary. The curriculum redesign resulted in a three-day, six-hour program:

● Day 1: A first, preparatory session in the classroom

● Day 2: An excursion to the forest

● Day 3: A concluding session in the classroom

The first tests in Spring 2022 provided a wealth of feedback about the program, used to make adaptations for subsequent cohorts.

Program design was guided by three key characteristics:

Positive

Though awareness of climate issues is important, UdN believes the current discourse on the negative impact that humans have on nature instills fear, anxiety, and feelings of helplessness, especially in our youth population. Research from the University of Bath cited at the beginning of this report shows that climate anxiety impacts the mental health and functioning of almost half of young people polled. UdN programs aim to furnish youth with a more positive approach that focuses on how nature can help us, and how we can help nature. Guilt has limitations as a motivational tool, as well as moral implications for its affect on children. UdN aims instead for students to feel empowered, and proud to be part of the solution.

Cognitive & Sensitive

In order to create a connection or build a relationship with something, we have to both know it on a cognitive level, but also experience it on a sensitive one. UdN’s approach recognizes that youth will not care about something they don’t know, and this is why programs are built on cognitive and emotional levels.

This sets UdN’s curriculum apart from traditional educational approaches which focus only on the cognitive—naming things and their parts, and describing in textbook terms how things work. Seldom are students asked how they feel. The difference in this approach may manifest in the following ways:

Student sees a picture of a plant in a textbook or on the screen.

vs.

Student experiences a plant in the wild by touching it and observing its growth.

Student receives information about the extinction of plant life.

vs.

Student finds out through direct experience how plants are different and similar to humans, and about their potential to help humans.

Student reads about the human causes for the extinction of plant life.

vs.

Student engages in moral discourse about the natural world, including questions like:

Do I like the way this plant smells?

Can plants make sounds we can hear?

When you cut a branch from a tree, will the tree feel pain?

Do trees have a sense of touch?

Can crows remember the face of a human?

How are trees similar to us?

The latter experiential approach is necessary for building a positive relationship with the natural world, and this marriage of the cognitive and the sensitive stands at the heart of UdN’s programs.

Reconciliatory

In addition to the importance of knowing nature, feeling part of it is another predictor of how much we will care about it. Humans and nature are not in opposition—we are part of nature as much as nature is part of us. People, especially young people, must feel a sense of this reconciliation with the natural world again in order to activate the motivation to change. UdN’s goal is to develop in students a conscious relationship with nature that transcends them as individuals, and places them within the larger, living ecosystem. The dimension of environmental identity is now seen as a major prerequisite for the ecological transition (Clayton, 2003).

PROGRAM STRUCTURE

As explained above, the final project was executed in three phases:

1. Introduction in the classroom (50 min)

A short introduction about L’Université dans la Nature was followed by exercises, presentations and prompts that tried to answer the question: Are humans a part of nature or not? By looking at the evolution of the Earth and the human species, students were allowed to reflect on the role nature played in our past and how this has changed over time. They were also invited to express their insights, feelings, and concerns about this change.

2. Excursion in the forest (3-4 hours)

The day started with a short questionnaire asking students questions about nature—to which they received the answers during the forest activities. They were also asked to report on their relationship with nature, as well as their general mood going into the day.

Then, students were taken (in most cases) to a forest in Ernzen, Larochette. This forest was chosen for its variety of plant life and relative silence, often difficult to find within Luxembourg.

Once in the forest, a short introduction reviewed the topics discussed in the classroom. Students were asked to explain their relationship to nature. For example, they could share how often they would go to the forest and the activities they would do there. Then the guide took the students through the following stages:

a. The first stage discussed the similarities and differences between the forest and the places where we live, and between trees and humans.

b. The second stage was dedicated to stress, exploring the different situations that cause stress and the activities we could do to feel better. Parallels were drawn between humans and animals and plants. The students were guided in brainstorming ways that nature might help us feel less stressed. A breathing exercise was taught to, and performed by, the group.

c. The following four stages were based on sense exploration: Touch, sight, hearing and smell were briefly discussed and explained. Every sense had its own nature-based activity, accompanied by an explanation of the benefit of nature-based sense exploration. The senses are rarely investigated in traditional teaching, but they play a key role in nature and provide an ideal opportunity to give them the importance they deserve. Students were posed the question of whether plants had these senses, and were provided with answers that scientific research has uncovered.

d. A final scavenger hunt tied all the concepts together and marked the end of the time in the forest.

Back in the bus, students were surveyed again on their mood and perceived relationship with nature.

3. Discussion in the classroom (50min)

Students had the opportunity to ask about and reflect on everything explored. In small groups, they discussed the various topics and activities from the previous two sessions. Then, they were asked to report out three things they liked and three things they didn’t like. They filled out a final evaluation of the program. As a last activity, they were asked to write a letter to a tree.

DEMOGRAPHICS

The program was designed for, and delivered to, high school students.

A total of 15 classes participated in the project offered from Spring 2022 until Spring 2023, including five “Préparatoire” classes, seven “Générale” classes, and three “Classique” classes.

This resulted in delivery to 271 students and 25 teachers from the following schools:

Lycée des Arts et Métiers (nine classes)

Lycée Athénée de Luxembourg (three classes)

Lënster Lycée International School (three classes)

Students from 7ème and 6ème level classes meant that students were between 11 and 16 years old, with 57% of the students identifying as male, 40% as female, and 3% as other.

Of the 271 students, there were:

Two students with visual deficiencies

One student with physical disabilities

Seven students with learning disabilities

RESULTS

The students’ reconnection with nature, their nature-based stress reduction, and improved feelings of agency in relation to climate issues were evident. Outcome measurements included their feedback during the course of the program, the thoughts and sentiments expressed in the questionnaire form completed before and after the forest experience, as well as through a culminating writing assignment.

One of the ways the program aimed to reconnect students with nature is through their cognitive understanding of the forest ecosystem. Sparking their curiosity, uncovering new mysteries, understanding the workings of the “boring” or “immobile” forest around them, and learning how we are connected to this ecosystem, were all key to the curriculum.

Here is a student recall on the element of the curriculum which covered tree communication networks:

“I didn't know that trees could communicate with each other.”

“I learned about how trees communicate with each other.”

“Trees can send ‘warnings’ to their neighboring trees to protect themselves.”

“I learned that trees can communicate in many different ways and can help other trees lacking nutrients by sharing them through their roots.”

They learned about the sensory world of plants:

“Trees have senses just like us, and they use them.”

“I learned that trees can sense us.”

“I learned that plants know when we are present in their area.”

“Plants can feel, hear, and see similar to humans. I find that astonishing.”

“Plants can detect when a bee approaches and make their nectar sweeter.”

“I found it fascinating that trees ‘see’, ‘feel’, and ‘communicate’, and it made me realize that trees and other plants are not as simple as I thought.”

“Trees grow straight because they can sense the Earth's gravity and balance their weight occasionally.”

“I learned that everything in nature is just like us, human beings.”

“I didn't know that plants and trees can feel, but now I know, and I think it's good to be aware of that.”

They gained insights about the soil beneath their feet and its benefits:

“There are more living organisms in a handful of soil than there are humans on this planet.”

“I learned that smelling the earth is good for you because there are no harmful bacteria in it.”

“There are very beneficial bacteria in the soil, which are used to make pills.”

“It's good for you to breathe in the forest soil.”

“Breathing in the soil in the forest is beneficial for us.”

They discovered new facts about the world and its inhabitants:

“I learned that nature on Earth has evolved very slowly.”.

“The oldest tree is 4853 years old.”

“I learned how to determine the age of trees.”

“I learned about the vast size a tree can reach.”

“I discovered a new plant called Venus.”

“A crow places its nuts on the road for a car to run over them.”

“Crows can remember human faces.”

“I learned how a dog sees.”

Additionally, they learned about our relationship with nature and what it has to offer them:

“I learned how to treat nature better.”

“I learned that we spend so much time indoors that we barely connect with nature the way our ancestors did thousands of years ago.”

“I learned to respect nature more, and I now realize it's more important than I thought.”

“Nature can calm people and bring joy.”

“We all have an emotional connection with plants.”

“Nature helps one feel better.”

“I discovered how peaceful silence can be.”

“I realized how loud nature actually is.”

Another key objective was to create positive overall experiences in the forest which lowered stress levels and brought a sense of enjoyment and/or peace. This was clearly met:

“I enjoyed it very much. I hope that many people can experience something like this.”

“It was fun, and I learned something new.”

“It was interesting.”

“Spending a day in the forest was fantastic, much better than sitting in school for 5 hours.”

“I found the activities excellent because we were in the forest, outdoors, and learning simultaneously. If we were indoors, the message wouldn't be as impactful as it is now.”

“I really like this walk.”

“It was a good and positive day.”

“Being in nature helps you relax when you're sad.”

“I learned to work in a group and help others.”

“The walk felt like a break from everything; it was peaceful.”

“The activity made me feel much calmer.”

“It was lovely to walk in the forest and not just talk in the classroom.”

“I found it so beautiful.”

“Everything was so beautiful and peaceful.”

Finally, the reconciliation with the natural world instilled a sense of empowerment and agency:

“I really liked the activity; it was very fun, and afterward, I felt differently towards nature in a positive way. I learned many new things that surprised me a lot.”

“Nature is much more complex than I thought, and I should spend more time there.”

“I enjoyed it very much, and I will spend more time in nature.”

“I felt a new breath and got to know the world.”

“I absolutely adored the birdsong, and the fluttering of the wind was incredible. I liked the sounds I heard.”

“We should show the world how beautiful nature is.”

Before and after the activity in the forest, students were asked to reflect on a series of images depicting human figures intersecting with nature, then answer the question: “Do you feel like you are a part of nature or not? Which image best describes your feeling?” The number of students who felt cohesion with nature jumped from nearly 6% before the forest experience to nearly 15% afterwards. The following graph visually summarizes their responses:

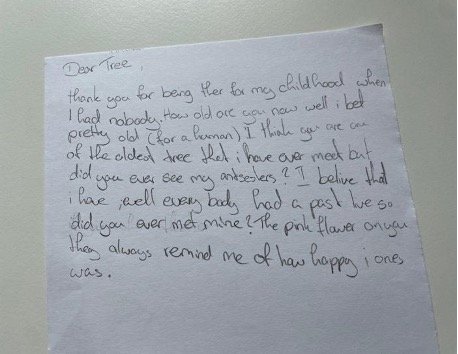

The last reflection task asked students to write a letter to a tree. To some, it seemed a foreign and weird ask, but after understanding that there were no limits set to their creativity or level of sharing, they eagerly took up their pens and they began to write.

This activity resulted in hundreds of letters, many of which are very moving and provide further qualitative evidence that high school students, when supported and encouraged, demonstrate real connection with the natural world.

Below is a sampling of four of these letters:

IMPACT

A simple, yet worrying example underlining the need for a positive approach to nature were the responses received to the question, “Are humans a part of nature?” Up to a third of students believed humans were no longer a part of nature. Even more alarming were the arguments given, the most prevalent of which was, “Because humans destroy nature.” Other explanations included:

Because humans pollute everything

Because we have distanced ourselves from nature

Because we leave our trash in the forest

Because we created a culture and society that we are a part of

Because we no longer respect nature

Because we believe ourselves to be above nature

Because we have no place and no purpose in nature

These arguments are not invented, but rather reflect the attitudes and beliefs of the wider society which the students are becoming part of—a society with an increasing disconnection with nature. Research shows the devastating effects of this disconnection on the mental health of students, creating a variety of eco-anxieties that in some cases affect their daily living.

Even more damaging, the perception that we are not part of nature creates the attitude that humans are bad for nature, further deepening the rift between humans and nature—one of the main causes of environmental destruction. We often ask which planet we are leaving our children, but at the same time we need to ask ourselves which children we are leaving our planet.

These students are in the midst of completely losing the experience of nature, what Robert Pyle named “extinction of experience” (1978). The students’ arguments above underscore this, as well as the many questions asked throughout the course of the program, including “How do trees actually grow?” and “What is this orange insect?” when pointing to a slug. Students’ initial uneasiness entering the forest—the disgust of the mud, the fear of all insects, the reluctance to touch or smell anything, or to sit down on the forest floor—also provide evidence of the loss of natural experiences within their generation. This loss not only diminishes access to the well-documented benefits to health and well-being, but also implies a cycle of disaffection towards nature.

However, the impact of the program on reclaiming these experiences for students is clear. Program administrators observed many changes in students throughout the course of the program—their body language became less rigid, their steps wandered further off the trail, and their eagerness to explore the natural world with all of their senses greatly increased.

Children need opportunities to interact with nature again. Children need adults in their life to instill within them a motivation that is built on positive experiences, on feelings of awe, wonderment, respect, caring, and—most of all—belonging. Quite simply, children need to feel good about being humans and this can be accomplished by showing them the many positive things we can do for the world around us. It is our moral obligation to give children hope that a different world is possible, and this program offers an effective springboard to accomplishing this.

Sources

Clayton, S. (2003). Environmental identity: A conceptual and an operational definition. In S. Clayton & S. Opotow (Eds), Identity and the natural environment: The psychological significance of nature (p. 45-65). MIT Press.

Hughes J., Rogerson M., Barton J., & Bragg, R. (2019) Age and connection to nature: when is engagement critical? Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/332132550_Age_and_connection_to_nature_when_is_engagement_critical

Marks, E, et al. (2021). Young People’s Voices on Climate Anxiety, Government Betrayal and Moral Injury: A Global Phenomenon. Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_ id=3918955

Pyle, Robert. (2009). The Nature Matrix. Available at: https://www.counterpointpress.com/books/nature-matrix/